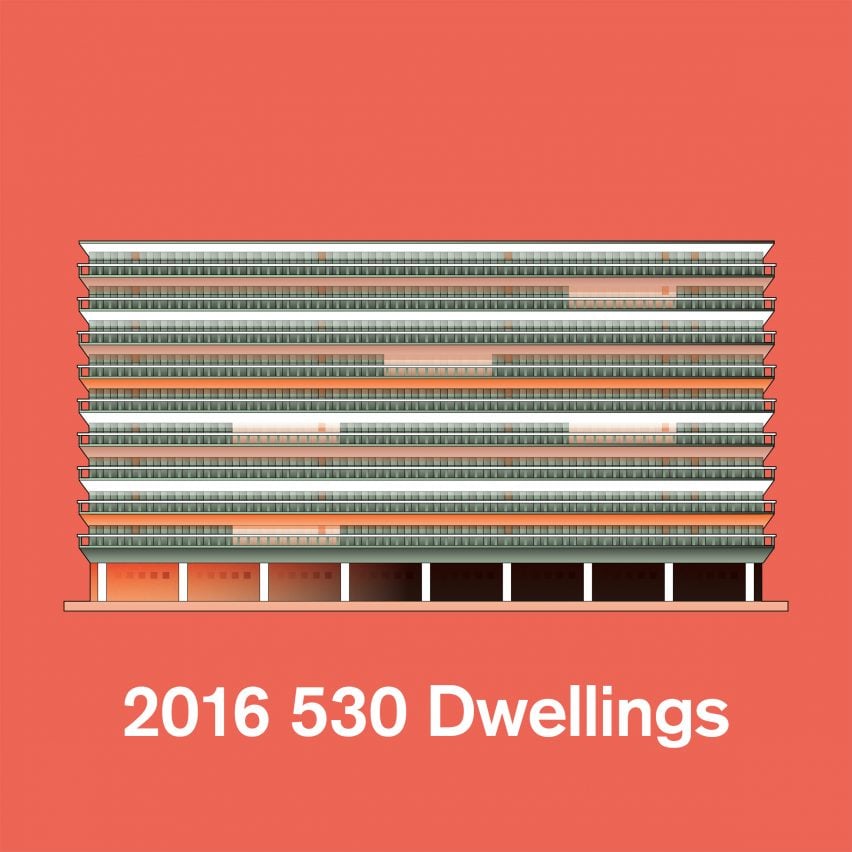

Next in our 21st-Century Architecture: 25 Years 25 Buildings series we look at the updating of three 1960s housing blocks in Bordeaux, which put social housing retrofit at the top of the architectural agenda.

Undertaken by French studios Lacaton & Vassal, Frédéric Druot Architecture and Christophe Hutin Architecture, the Transformation of 530 Dwellings not only demonstrated to France’s government that there was an alternative to demolishing its much-maligned social housing stock, it showed how much could be achieved with relatively little.

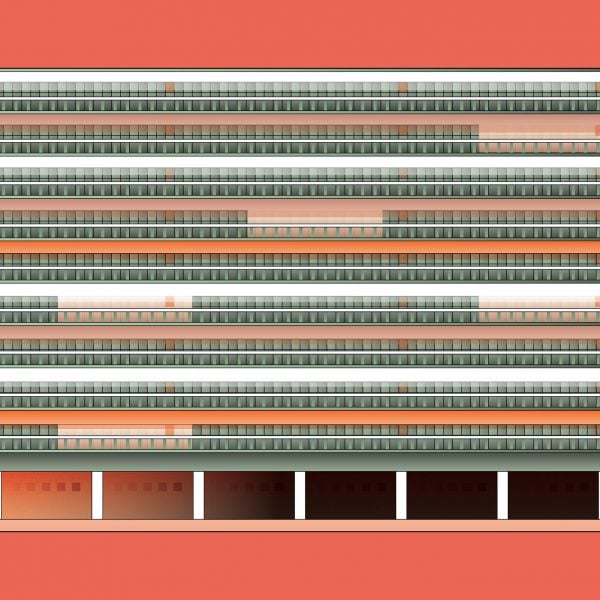

By expanding each housing block with a simple facade of polycarbonate-clad winter gardens, this understated retrofit embodied the ethos that Lacaton & Vassal founders Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal had been quietly pursuing for decades – “never demolish, always transform”.

When the project won the Mies van Der Rohe Award in 2019, followed by Lacaton and Vassal themselves being awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2021, it brought global attention to this ethos, which could hardly have resonated more with a new generation of architects confronting joint environmental and housing catastrophes.

The fact that two of architecture’s most prestigious awards chose to recognise the masters of restrained retrofit was hailed as a significant shift in architectural values and responsibilities, with the Pritzker Architecture Prize Jury calling their work “an adjusted definition of the very profession of architecture”.

As David Huber wrote in Metropolis magazine, “they don’t rattle off the names of de rigueur philosophers or prattle on about ‘the future of architecture’. They haven’t done a TED Talk. And yet their work is more urgent than that of most of their peers, since they are advocating for buildings that would otherwise be demolished.”

While global recognition re-framed Lacaton & Vassal’s work, the duo had since their formation in 1987 been exploring how shoestring budgets, simple gestures and ordinary materials could be used to maximum effect, whether for a private house or a contemporary arts centre.

The Transformation of 530 Dwellings, also known as Grand Parc after the name of the housing estate, was one of a series of projects that marked a concerted move into the realm of social housing. The impetus came in 2004, when the French cultural ministry announced billions of euros of funding for urban renewal schemes.

In the case of the country’s often-maligned post-war social housing developments, the true meaning of this “renewal” – a euphemism many across Europe will be familiar with – meant knocking them down in order to create smaller, more expensive housing.

“It was great that, finally, there was money available for underprivileged neighbourhoods, but we felt it should be used the right way,” Lacaton told The Architectural Review.

In response, Lacaton & Vassal, along with former classmate Frederic Drurot, authored a manifesto entitled Plus, or “more”, in which they drew up a series of case studies that demonstrated how, through simple, economic gestures, these estates could not only be renewed but made better for their residents than they ever had been – all for less money than demolition and reconstruction.

This manifesto was where the duo first coined what would become known as their mantra: “never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform, and reuse!”

Two key projects followed: the Cité Manifeste, for a housing collective in 2005, and the renovation of the Tour Bois-le-Prêtre in Paris with Frédéric Druot Architecture in 2011.

Tour Bois-le-Prêtre laid the groundwork for the Bordeaux scheme, not least in giving its residents the reassurance that its architects were not in cahoots with “the men in suits, the enemy”, as Lacaton put it.

Apparent both in the manifesto and in Lacaton & Vassal’s previous housing projects was a gesture that would become a defining one for the architects, and particularly at the Transformation of 530 Dwellings – the winter garden.

Drawing on a diverse range of influences, from historic glasshouses and agricultural greenhouses to the Case Study House programme, these gardens were a scaffold-like framework affixed to the exterior of existing buildings, replacing often tired, small-windowed facades with full-height polycarbonate walls.

Rarely has Mies’s famously gnomic aphorism ‘less is more’ seemed so aptCatherine Slessor in The Guardian

Not only did this insulate the block – the studio refer to it as “living insulation” – but added vast amounts of usable space at the same time, and when the polycarbonate screens are slid open they lead to balconies providing panoramic views of Bordeaux.

Prefabricated in concrete and steel, the winter gardens provide each of the 530 apartments in the Grand Parc project with an additional 3.8 metres of depth – for some amounting to a doubling in size – installed without residents needing to move.

“You have a person who’s lived in the same space for 30 years with a tiny little window and, all of a sudden, there are sweeping views and 25 to 30 square metres of extra space, and they start to think, ‘I could put the table over there, a sofa here, plants at the balcony’, and something quite astonishing happens,” Anne Lacaton told The Architectural review about the strategy.

Half of the project’s budget went towards these winter gardens, and the other half towards more general upgrading. None of this, however, fundamentally changed the existing architecture of the block, with Lacaton & Vassal preferring to simply provide the maximum amount of space and light that residents could then adapt as they wished.

Costing a total of around 65,000 euros per apartment, this was a remarkable combination of benefits into a single, straightforward structural intervention, embodying another of the duo’s mantras: “economy is not a lack of ambition, but a tool of freedom”.

Writing in The Guardian, Catherine Slessor remarked how “rarely has Mies’s famously gnomic aphorism ‘less is more’ seemed so apt”.

As multiple crises see architecture hunt for where its most impactful purpose lies, Lacaton & Vassal’s work continues to provide a resolute answer – not in heroic formal gestures, but in making better what we already have so that it works best for those who need it.

“When you go to the doctor, they might tell you that you’re fine, that you don’t need any medicine,” Vassal told The Guardian in 2021.

“Architecture should be the same. If you take time to observe, and look very precisely, sometimes the answer is to do nothing.”

Did we get it right? Was the Transformation of 530 Dwellings in Bordeaux the most significant building completed in 2016? Let us know in the comments. We will be running a poll once all 25 buildings are revealed to determine the most significant building of the 21st century so far.

This article is part of Dezeen’s 21st-Century Architecture: 25 Years 25 Buildings series, which looks at the most significant architecture of the 21st century so far. For the series, we have selected the most influential building from each of the first 25 years of the century.

The illustration is by Jack Bedford and the photography is by Philippe Ruault.

21st Century Architecture: 25 Years 25 Buildings

2000: Tate Modern by Herzog & de Meuron

2001: Gando Primary School by Diébédo Francis Kéré

2002: Bergisel Ski Jump by Zaha Hadid

2003: Walt Disney Concert Hall by Frank Gehry

2004: Quinta Monroy by Elemental

2005: Moriyama House by Ryue Nishizawa

2006: Madrid-Barajas airport by RSHP and Estudio Lamela

2007: Oslo Opera House by Snøhetta

2008: Museum of Islamic Art by IM Pei

2009: Murray Grove by Waugh Thistleton Architects

2010: Burj Khalifa by SOM

2011: National September 11 Memorial by Handel Architects

2012: CCTV Headquarters by OMA

2013: Cardboard Cathedral by Shigeru Ban

2014: Bosco Verticale by Stefano Boeri

2015: UTEC Lima campus by Grafton Architects

2016: Transformation of 530 Dwellings by Lacaton & Vassal, Frédéric Druot and Christophe Hutin

This list will be updated as the series progresses.