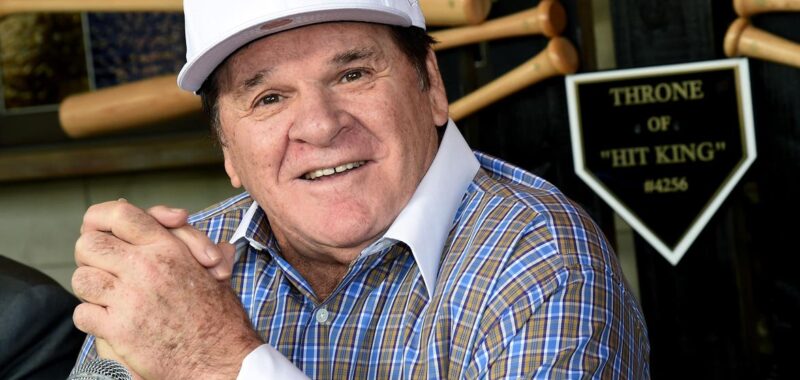

LAS VEGAS, NV – DECEMBER 15: Former Major League Baseball player and manager Pete Rose speaks … More

Regarding Pete Rose’s release Tuesday from the Major League Baseball slammer, here was the good, the bad and the ridiculous in one statement: MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred announced the man who lived his nickname of “Charlie Hustle” throughout his playing career is no longer permanently banned from the sport.

Good.

Here was the bad: The timing.

I mean, why didn’t those in charge of such things set Rose free years or even months before his death last September at 83 in his Las Vegas home?

As for the ridiculous, well, anybody who could distinguish a catcher’s mitt from a Cracker Jack box knew as soon as Rose quit breathing, he would get reinstated into the game.

Guess who knew that the most?

Yep, it was Rose. As a baseball historian, he knew common sense and his resume would combine at some point, but he suspected it would come after his death. So sad, so unnecessary, so ridiculous. He was unofficially a Baseball Hall of Famer by the end of his 24 MLB seasons through 1986, and his worthiness for Cooperstown went beyond his record 4,256 career hits.

Now Rose officially can reach the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2028.

First, the Historical Overview Committee must nominate Rose for the 2027 Classic Baseball Committee ballot, and then he would need 12 votes from that 16-member committee of four former players, four executives and four historians to receive his bronzed Cooperstown plaque.

He’ll get it.

But let’s shove more of the ridiculous out of the way. For one, Manfred’s declaration Tuesday should have been about Rose, period.

Instead, Manfred sifted through more than 100 years of baseball’s considerable archives, and he yanked the lifetime ban from Rose as well as from all of the others among the deceased. “Obviously, a person no longer with us cannot represent a threat to the integrity of the game,” Manfred wrote to attorney Jeffrey M. Lenkov, who petitioned for Rose’s removal from baseball’s slammer.

NEW YORK, NY – MARCH 27: Christian Yelich #22 of the Milwaukee Brewers talks with Major League … More

Manfred granted Lenkov’s wish for Rose, which also was encouraged (OK, urged) by President Donald Trump at the White House in April, and then Manfred got pardon happy. He should have saved the ones for Shoeless Joe Jackson and the other Black Sox folks for another day.

Now the floodgates of questions keep threatening to drawn out the most important thing here, and among those questions: Will the commissioner revist the punishments for the cheating Astros of 2017 and their trash cans?

What about the Cooperstown damage done to Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Alex Rodriguez and the rest of those steroid guys?

Should they all get pardons?

You know, even the trash cans?

Rose was the most important thing here. It deserved a separate ruling for a scrappy player who often bragged about becoming “the first singles hitter to make $100,000.” The Cincinnati Reds made that happen in 1970 for their hometown player when such salaries were reserved for sluggers.

Later, after the 1978 season, Rose shocked the baseball world by bolting his childhood team to sign a free-agent contract worth $3.2 million for four years with the Philadelphia Phillies. He was the highest-paid baseball player in history at the time (In contrast, half of the 30 MLB teams in 2024 had at least one guy making $25 million or more), and Rose probably was underpaid. He once told me he held the all-time record for playing in the most winning games by a pro athlete.

In fact, Rose told me many things.

When Terence Moore worked for the San Francisco Examiner, he interviewed Pete Rose in August 1984 in … More

Our connection began during a September night in 1969 at legendary Crosley Field in Cincinnati, where my 13-year-old self watched from the stands as the Reds’ leadoff hitter and right fielder became my all-time favorite player in a flash. His head-first slides, his sprints to first base after walks, his ability to make you not wish to take your eyes off him for a millisecond.

That was Rose forever.

As the baseball gods would have it, our connection grew through my decades as a professional journalist.

I covered Rose with the Reds during the late 1970s when I worked for the Cincinnati Enquirer. I joined other media folks in September 1985 along the Ohio River at Riverfront Sadium when he broke Ty Cobb’s career hits record. I also was there when he called a press conference at Riverfront Stadium in August 1989 to say he did not bet on baseball, but the MLB cops said otherwise. He received his lifetime band from then-commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti.

Fay Vincent followed Giamatti, and then came Bud Selig in 1998, and Manfred has been baseball’s head man since 2015. That’s when he first rejected one of Rose’s many attempts at receiving a parole from his lifetime ban.

Rose went from saying he didn’t bet on baseball to sort of claiming he did (but not on or against the Reds) to confessing so much that tears flowed from his eyes before his former Big Red Machine teammates of 1970s lore. That was during a September 2010 gathering in Lawrenceburg, Indiana of the old gang of Hall of Famers and near ones.

MLB officials weren’t moved.

Nevertheless, Rose told me in September 2015, when we both were at my alma mater of Miami University in Oxford, Ohio that he eventually would reach the Baseball Hall of Fame “probably when I’m dead.”

Ten days before Rose’s death, he went further than that with Dayton, Ohio sportscaster John Condit.

“I’ve come to the conclusion — I hope I’m wrong — that I’ll make the Hall of Fame after I die,’’ Rose told Condit. “Which I totally disagree with, because the Hall of Fame is for two reasons: your fans and your family. That’s what the Hall of Fame is for. Your fans and your family. And it’s for your family if you’re here. It’s for your fans if you’re here. Not if you’re 10 feet under. You understand what I’m saying?

“What good is it going to do me or my fans if they put me in the Hall of Fame couple years after I pass away? What’s the point? What’s the point? Because they’ll make money over it?”

Yes, they will.

And nobody among the “they” will be named Peter Edward Rose.