In keeping with our annual tradition, we asked three of our critics for their favorite books of the last year. Between them, they chose 15 books, three of them reissues, and the majority fiction. The selections include the latest works from a literary power couple — Percival Everett’s “James” and Danzy Senna’s “Colored Television” — as well as offerings from first-time novelists. The diverse narratives tackle thorny topics such as illness, racism and the dissolution of marriage; one selection employs experimental storytelling that shouldn’t work but does, while another is positively Joycean in its length. Our critics’ choices overlapped twice, and in those cases their reviews follow each other on this alphabetically arranged list. Happy reading.

“Alphabetical Diaries”

By Sheila Heti

Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 224 pages, $27

Heti is one of the freest writers and thinkers I know. With her latest book, she took 10 years of her diaries and alphabetized them by the first letter of the first word of each sentence, then cut the book down into the volume published. One might think “Alphabetical Diaries” would be a challenge to read, or flat-out nonsensical. Instead, it is a devotional text that asks questions and answers them, takes those answers back and rotates them over a spit, like a rotisserie of art and writing. It is an absolute delight.

— Jessica Ferri

“Cahokia Jazz”

By Francis Spufford

Scribner: 464 pages, $28

In this superb speculative novel, Spufford imagines that Manifest Destiny hit a roadblock in the Midwest: The region around St. Louis isn’t Missouri and Illinois but Cahokia, ruled by the Native tribe there. But while Indigenous Americans have more autonomy, racism is as persistent as ever, and the novel is a bracing tale of a brewing race war in the capital city in 1922. The novel is plainly an allegory for America’s current fraught moment, but it’s also a lively neo-noir filled with tough-talking detectives, politicos and journalists, and rife with canny plot twists. Spufford, a Brit, conducted enough research to credibly imagine this milieu, and its smarts about race and religion never feel ponderous or forced.

— Mark Athitakis

“Colored Television”

By Danzy Senna

Riverhead Books: 288 pages, $29

It must be very rare, if not unheard of, for a pair of married writers to have books on the same best-of-the-year list, but here we are in 2024, and Senna has written a superb comic novel, while her husband, Percival Everett, has written a superb literary novel. “Colored Television” follows another married pair of creatives, Jane and Lenny, who, along with their two children, relocate from Brooklyn to Los Angeles. He’s a visual artist, she’s a novelist and professor. He identifies as Black; she is multiracial and comfortable using the word “mulatto” to describe herself. Even as the pair discuss race and racism, “Colored Television” is a book about the age-old tension between living as makers and making a living. When Jane takes on a TV writing project, she neglects her artistic work. But what Senna shows, carefully, is that even age-old questions are complicated when the people trying to answer them are African Americans.

— Bethanne Patrick

“Great Expectations”

By Vinson Cunningham

Hogarth Press: 272 pages, $28

Inspired by Cunningham’s experience working for Barack Obama’s first White House campaign, this emotionally nuanced first novel follows the narrator, David, during his at once inspiring and dispiriting experience working for an unnamed presidential candidate. Inspiring, because as a Black man, David can see the opportunities the candidate represents for him in terms of power and respect. Dispiriting, because all of the disappointments and ugly compromises of retail politics are in full view. Along the way, Cunningham delivers bracing, thoughtful commentaries on relationships, music, film, race and more. Cunningham, a New Yorker staff writer, is a perceptive cultural critic, and in this first novel a fine storyteller as well.

— M.A.

“James”

By Percival Everett

Doubleday: 320 pages, $28

Everett’s inversion of Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” told by the eponymous James, allows its narrator to reclaim both his proper name and history from the character Twain simply called “Jim.” Everett riffs (a deliberate word choice, since jazz plays an important role in this novel) on a different view of Black American life than Twain ever could have but also manages to demonstrate that it contains as much laughter, irony and comedy as the entire slate of Mark Twain Prize for American Humor winners. We know this because James reads and writes, despite the risks he courts through those acts; we know that James is also engaging in a kind of double narrative arising from W.E.B. Du Bois’ double consciousness. Even as he details his adventures, often dangerous, James knows white people will never understand everything he’s trying to say, which is what makes this partial homage a masterpiece in full.

— B.P.

“Leaving”

By Roxana Robinson

Norton: 344 pages, $29

A study once found the emotional effects of divorce on children are similar whether those children are 3 or 30. In Robinson’s brilliant take on late-life love, long-married Warren contends with family anger when he meets up with his long-divorced college flame, Sarah. In an era where we have few obstacles to affairs, this scenario works; Warren’s daughter Kat is at once an avatar of umbrage and of loss. Robinson employs the would-be lovers’ various forms of privilege to great effect; their resources allow them time to think carefully about what they might give up, and what they might anticipate, should things continue. Warren does choose to return to his wife. However, Robinson, who often covers tough subjects (a soldier’s homecoming in “Sparta”; addiction in “Cost”), delivers a shock of an ending that, like her premise, rings true.

— B.P.

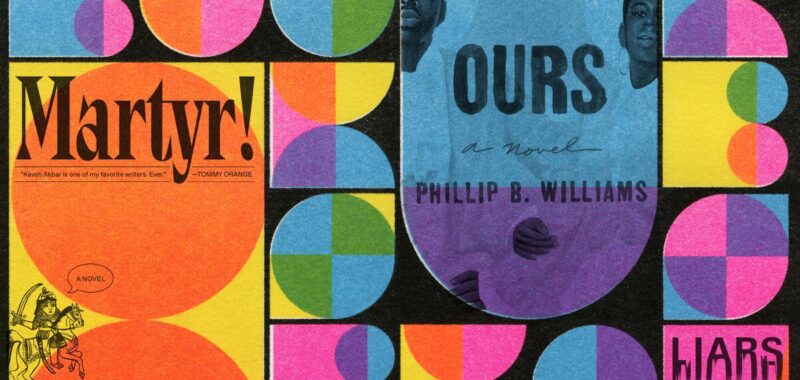

“Liars”

By Sarah Manguso

Hogarth Press: 272 pages, $28

“I was a layer cake of abandonment and hurt and fury, iced with a smile,” goes a typically curt, sardonic line in Manguso’s second novel, which chronicles the slow-motion collapse of a marriage. The narrator, Jane, is a writer married to an artist, John, who’s increasingly consumed by jealousy and a competitive streak. The plot has a sense of inevitability — we can see the end coming well before the protagonists do — but Manguso’s poised, careful chronicle of Jane and John’s story is engrossing, as Jane finds herself struggling to escape a web of gendered, sexist roles and questions her own complicity in her marriage’s breakdown. In the process, she revivifies the domestic-drama novel, escaping its cliches and intensifying its mood.

— M.A.

“Liars”

By Sarah Manguso

Hogarth Press: 272 pages, $28

Marguerite Duras famously wrote “that people kill themselves because of my books won’t stop me from writing,” which is my mantra when it comes to women writing fiction, or women writing anything at all, or people of any gender writing anything about anything. Nothing makes me angrier than readers telling me they didn’t like a narrator, or that they wanted to hear a different side of the story. Manguso’s “Liars” is a punishing, unrelenting horror story about the total failure of heterosexual marriage told only from the wife’s point of view. Reading “Liars” is like being baptized by fire. This novel is a reminder that when it comes to art, it doesn’t matter whether or not people are nice or the story is fair. This is everything writing should be. “Liars” is the best book of the year and, in my mind, easily one of the best novels of the past 20 years.

— J.F.

“Martyr!

By Kaveh Akbar

Knopf: 352 pages, $28

Akbar’s sensitive and bitingly funny first novel concerns an Iranian American poet struggling with addiction recovery, the deaths of family members, and an identity that seems like it’s endlessly fracturing. He tries to write his way through the problem, dedicating poems to martyrs from Joan of Arc to IRA activist Bobby Sands. He conducts conversations in his head with Donald Trump and Lisa Simpson. He visits a dying artist for answers. None offer the clarity he craves, but the journey is a fine showcase for Akbar’s wide-ranging cultural awareness, self-deprecating humor — and a closing plot twist that suggests that the effort of working through our cultural confusions might eventually pay psychic dividends.

— M.A.

“Martyr!”

By Kaveh Akbar

Knopf: 352 pages, $28

Cyrus Shams, the protagonist of “Martyr!,” is a poet, comfortable playing with language. Sometimes he details his road trip from Indiana to Brooklyn; sometimes he creates imaginary conversations between, say, a basketball legend and an imaginary sibling; sometimes he just messes with words, describing his suicidal depression as a “doom organ.” He lives between life and death, his family’s native Persia and his Indiana childhood, and his bisexual desire. The artist he’s hoping to meet in Brooklyn, Orkideh, is also Iranian American. Terminally ill, she spends her last days as a living museum exhibit, chatting with any and all visitors. Cyrus hopes that Orkideh’s process will inspire his own epic poem, “The Book of Martyrs,” until she helps him understand the epic nature of living not between, but amid, different states.

— B.P.

“Miss MacIntosh, My Darling” and “Angel in the Forest”

By Marguerite Young

Dalkey Archive Press: 3,449 pages, $30 (“Miss MacIntosh, My Darling”); 438 pages, $18 (“Angel in the Forest”)

Blessings upon Dalkey Archive Press for reissuing these two epic books by Young that were long out of print. Young was a poet and critic, and she spent nearly 20 years writing her masterpiece, one of the longest American novels ever: “Miss MacIntosh, My Darling.” At 3,449 pages, the novel’s plot can be simply described as a Joycean voyage: A woman named Vera Cartwheel goes in search of her long-lost nanny, Miss MacIntosh. The same year she began work on the novel, Young published “Angel in the Forest,” a nonfiction account of two competing utopian communities in 19th century Indiana. Young’s sentences are some of the most beautiful I’ve ever read, wherein she is prone to gorgeous listing, so that it hardly matters whether her writing is fiction or nonfiction. “Our ancestors, always hurried,” she writes in “Angel in the Forest,” “left little evidence of their existence, if one discounts intangibles, a sundial, an apple a day, an angel in the forest.”

— J.F.

“My Brother”

By Jamaica Kincaid

Picador: 208 pages, $17

Another reissue, with lovely new cover art, is Kincaid’s memoir, “My Brother,” first published in 1997. Kincaid had not been to her birthplace of Antigua in 20 years when she receives word from her mother that her brother is sick. Upon arrival, it becomes obvious to Kincaid (though no one is speaking of it) that her brother is dying of AIDS. With Kincaid’s talent, her brother’s illness and subsequent death would make a desperately great book. But Kincaid goes further, ruminating on her life after Antigua, her decision to never return and to make herself a writer.

— J.F.

“Ours”

By Phillip B. Williams

Viking: 592 pages, $32

Author Williams follows a fictional all-Black town called Ours in Missouri from its establishment in the 19th century to our own time with a mixture of realism, the paranormal and the lyrical. It allows him to create a place that starts as a utopia and ends as disappointment because, as one of the characters says, “Freedom didn’t mean safety.” A formidable woman named Saint enchants the borders of Ours in 1834 so that freed slaves might live without the interference of white people; any of the latter who try to find their way in encounter the same clump of trees again and again. But when you put a spell on one thing, other types of magic find their way in, and not all of them are benign. Some residents live in fear, not of enslavement but of their own visions; others wind up traveling to the future and return with sad truths. Everyone involved must reckon with what it means to remain set apart from the rest of the world.

— B.P.

“The Safekeep”

By Yael van der Wouden

Avid Reader Press: 272 pages, $29

Isabel, unmarried, priggish and devoted to her housekeeping routine, lives alone in her family’s home, ostensibly keeping it safe for the brother who inherited it. When that brother brings home a slightly outlandish girlfriend, then allows her to stay for a few weeks while he’s away on business, Isabel is at first appalled. But slowly, and then quite quickly, she and the young woman, Eva, begin an affair of intense eroticism that heralds a book about sexual awakening. However, readers should note that the author’s every detail ties this first half of the Booker-nominated novel together with its unexpected and extraordinary second half. For example, during one lovemaking session, Isabel sees herself in a mirror and says that her face is red, “mouth like a violence.” Without spoiling Van der Wouden’s structure, readers can know that not all violence has to do with torture and death. A shard of pottery can foretell an act of abuse.

— B.P.

“Small Rain”

By Garth Greenwell

Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 320 pages, $28

Greenwell, whose novel “What Belongs to You” and short-story collection “Cleanness” redefined writing about sex and desire, here redefines writing about illness and dependency. “Small Rain” could technically be defined as autofiction, since it’s about a gay male writer (in this case, a poet) whose sudden, devastating physical injury mirrors the gay male author’s own COVID-era aortic tear and long hospitalization. However, the story pays scant attention to anything else fact-based, focusing instead on how pain and fear disconnect a person from life — and how acts of kindness bring them back. “Commonness didn’t cancel wonder,” writes Greenwell, whose fictional version of personal experience proves wondrous in its attention to recovery, from IVs and gurneys, on to caregivers and lovers.

— B.P.

“The Third Realm”

By Karl Ove Knausgaard

Translated from the Norwegian by Martin Aitken

Penguin Press: 493 pages, $32

Knausgaard doesn’t understand the concept of restraint: Be it in his celebrated six-volume autofiction epic “My Struggle” or this, the third volume of a series about the mysterious arrival of a new star, he aspires to pack as much as he can in one book. Here, the broad themes are resurrection, mental illness, mass murder and religious devotion. But despite such heady material, the book itself is pleasurably earthbound and uncomplicated, shifting from one character in his Norwegian ensemble to the next with charm and intelligence, blending the wonder of science fiction with the moody intensity of a murder mystery. Though there are two previous volumes in this series; this one, the best in the batch, stands well on its own.

— M.A.